|

|

|

Peace

at a price |

|

|

|

|

||

|

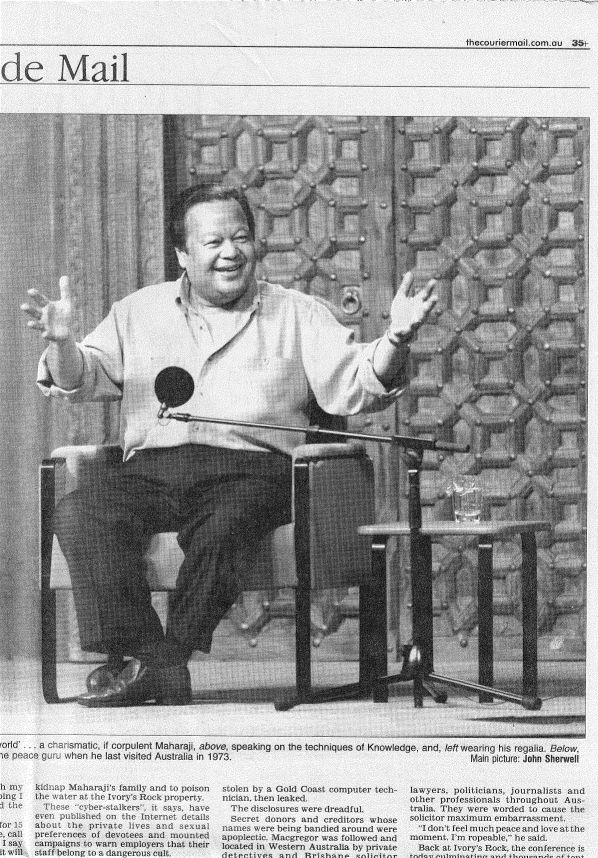

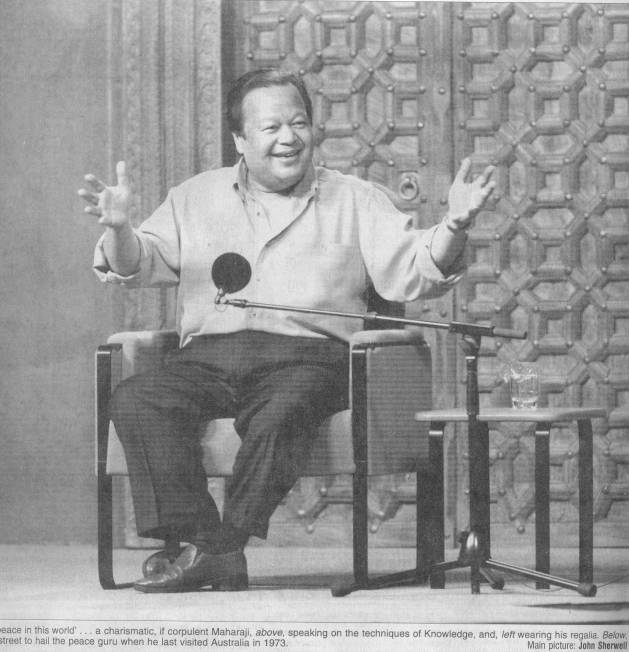

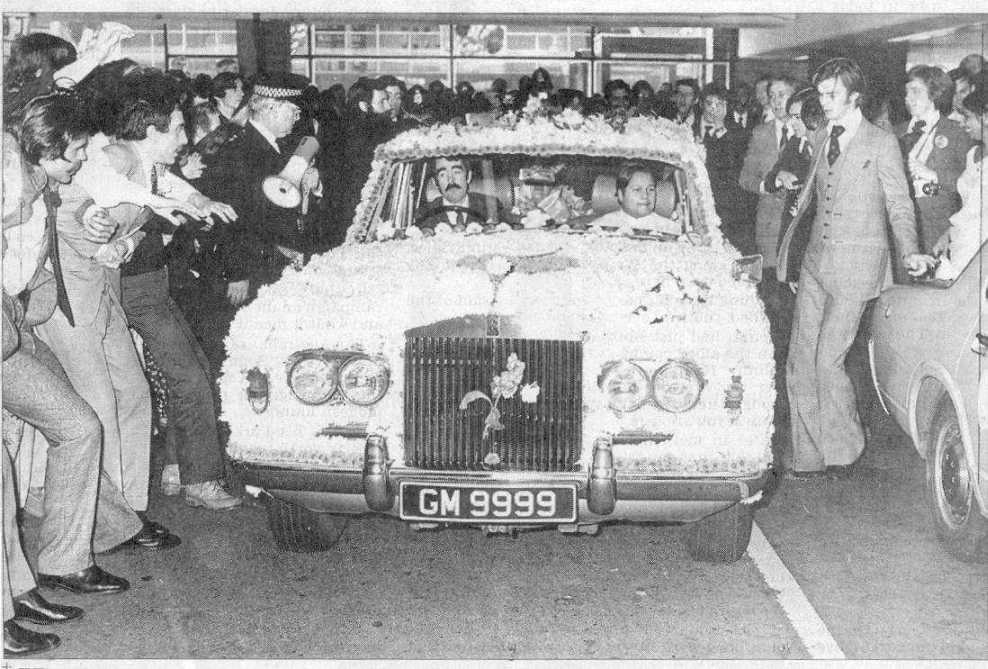

Thousands of devotees mill about the tent sites pitched for an international love-in with the Maharaji. But, as Hedley Thomas tells, there are unhappy campers trying to bring the affluent peace guru down a peg or two JIM Barrow lowers his voice and suggests a table out of earshot of a group munching McMuffins in the shadows of the golden arches on the outskirts of Ipswich. He and his wife, Maureen, don't readily trust strangers in these parts any more. Too many bizarre things going down, he reckons. Too close to the Maharaji and his devotees, more than 3000 of whom are streaming into the district -- in helicopters, limousines, buses and taxis -- for five days of peace and bonding at Peak Crossing. Barrow is carrying folders stuffed with documents. There's academic literature on Elan Vital, formerly the Divine Light Mission, and its extravagantly affluent guru, Maharaji (also known as Prem Rawat). There are tell-all confessions of former followers, who are waging an extraordinary cyberspace cult war against a man they once hailed as god-like, a "Lord of the Universe" but now condemned as a fraud. There are extracts from company and property searches identifying the legal and financial structure underpinning the Australian enterprise and its jewel, the Ivory's Rock Conference Centre at Peak Crossing, into which some $20 million has been poured. And letters and petitions from local residents, mostly rural farming folk like Jim and Maureen, who have read much about the guru in the decade since a company connected to his empire snapped up the land, but never met him. "If the Maharaji walked in here now, I'd get up and walk away," drawls Barrow, a retired US Navy chief petty officer whose farming property backs on to the 800ha of land controlled by Elan Vital. "It would turn my stomach just to see him. Anyone who can prey on people's uncertainties, who can promise people things that they have not found yet, is not a good person." Barrow complains that he's been butting his head against a bureaucratic wall for years in a bid to have Elan Vital Inc Australia, a registered non-profit association, investigated by the Australian Taxation Office and other authorities. He produces a chapter from Larson's New Book of Cults. It says: "In the early seventies, Guru Maharaji Ji commanded one of the largest and fastest-growing followings of all imported cult leaders." Other historical records paint a fascinating picture. As a teenager he led thousands through the streets of Delhi in 1970 declaring, "I will establish peace in this world." Tens of thousands of teenagers and young adults in the West left families, universities and jobs to commune in ashrams. In line with the guru's message, they sought enlightenment while abstaining from sex and alcohol during a quest for peace and the Knowledge. But when, at 16, the guru wed a former United Airlines flight attendant, who then promptly refused to let her mother-in-law set foot in the newly acquired Malibu mansion, things got really weird: Maharaji was denounced by his own mum as a "drinking, dancing, nightclub-haunting meateater", unfit to follow in his father's sacred footsteps. "At one time," according to the Book of Cults, "he confidently declared `The Key to the whole life, the key to the existence of this entire universe, rests in the hands of (me)'. Then it all fell apart." But not completely. It is a sunny breezy day behind Ipswich, perfect for a mass love-in amidst picturesque rural surrounds. Just 20km from where Barrow sits fulminating, a charismatic, if corpulent (he is said to enjoy fine cognac) cult figure smiles with a heavenly radiance. His followers, who have come from around the world to pay homage, and much more besides (all major credit cards accepted), walk contentedly through the park-like grounds between the private restaurants, coffee shops, amphitheatre and hundreds of tents. It is the most expensive camp site in Australia for the week: devotees who opted for the "deluxe" tent package paid $4000 a couple. Organisers hasten to add that "the techniques of Knowledge are taught free of charge without regard to a person's gender, economic or social status, sexual preference, lifestyle, race, religious or ethnic background"; and that about 230 devotees at Ivory's Rock this week paid nothing. During previous visits he stayed in a sprawling mansion at Fig Tree Pocket, but this time he's bunking down in a permanent tent, or "pent", so called, according to devotee and conference organiser Cath Carroll, "because their design is modelled on the shape of a tent but provides permanent cabin-style accommodation". While Jim Barrow obviously has concerns, Carroll says many other neighbours are very happy with a situation that creates jobs and pours money into the area. MAHARAJI'S

Elan Vital Australia people say simply that, "He

enjoys an affluent lifestyle and makes no secret

about it: his view is that neither poverty nor

riches brings fulfilment. "His

lifestyle is entirely supported by his own

personal business investments. Absolutely no

money flows from these organisations to him or

his family. "Since Maharaji left India in 1971, he has been audited several times. He has never been charged with any wrongdoing. Every time, the audits have had a completely positive and successful outcome." Maharaji rarely does media interviews but a few days before mingling with his devotees at Ivory's Rock, he gave a speech at Griffith University. "A lot of people are shocked with my message because they're really hoping I will give them a formula," he told the throng. "You know, `go stand on one leg for 15 minutes and if you don't feel peace, call me in the morning'. I don't do that. I say to people `peace is inside of you and it will be whether you make an attempt to feel it or not, it will always be inside of you'." But the self-indulgent opulence infuriates former devotees, some of whom for several years have been diligently filing millions of words about the Maharaji on to a website, (www.ex-premie.org). With the help of senior defectors they have analysed the financial structures and assets while recounting the poverty of devotees who blissfully handed over their own wealth. They ask questions like: "Was it not hypocritical to prohibit your followers from drinking and smoking or having sex whilst you did so yourself in private?"; "Why do you encourage your followers to line up and kiss your feet?"; "How can you claim to be a bringer of peace when you don't even get along with your own brother?"; and "Do you need your yacht, plane and wealth to spread Knowledge?" The depth of the Internet site and its detail on everything from the banality of his utterances, to photographs and title deeds of the mansion, have stung Maharaji and his remaining devotees into counter-strikes. Peace, apparently, is a flexible concept for a guru when he's coming under serious fire. Cath Carroll, an unfailingly polite devotee who runs Ivory's Rock, provides excerpts from the official website (www.elanvital.com.au) and characterises the critics as a small hate group hellbent on stalking and harassing Maharaji and Elan Vital. Among the critics, she says, are a crooked lawyer, a drugs trafficker, a paranoid maniac, an unethical journalist and a schizophrenic. "This is not exactly a cross-section of normal, ordinary, functional law-abiding citizens."*  Elan Vital dismisses the once-dedicated devotees as mental misfits who have incited people to drug and kidnap Maharaji's family and to poison the water at the Ivory's Rock property. These "cyber-stalkers", it says, have even published on the Internet details about the private lives and sexual preferences of devotees and mounted campaigns to warn employers that their staff belong to a dangerous cult. "Maharaji is simply motivated by his wish to help as many people as possible find within themselves the peace and happiness that he has found. "He does not receive any financial compensation or remuneration for his appearance." MUCH of Elan Vital's attention in recent months has been focused on John Macgregor, an Australian journalist who was a devotee for almost 30 years until he began to read the website and verify the information. "You can stay in denial for only so long," he says. Macgregor also published on the Internet confidential commercial information about Elan Vital which had been stolen by a Gold Coast computer technician, then leaked. The disclosures were dreadful. Secret donors and creditors whose names were being bandied around were apoplectic. Macgregor was followed and located in Western Australia by private detectives and Brisbane solicitor Damian Scattini, acting on behalf of Elan Vital. "I've been secretly filmed, followed, tape-recorded and watched outside my home," Macgregor says. Scattini won at every turn, succeeding in a series of Queensland Supreme Court actions which gagged Macgregor and led to adverse findings over his credibility. Scattini regards Macgregor as a liar and a misfit who broke the law. Macgregor says he has become accustomed to personal counter-attacks since he turned on Maharaji. But this week, Scattini, who is not a devotee, became the target of an Internet campaign: several thousand e-mails falsely purporting to have been sent by him were bounced into the inbox of lawyers, politicians, journalists and other professionals throughout Australia. They were worded to cause the solicitor maximum embarrassment. "I don't feel much peace and love at the moment. I'm ropeable," he said. "He knows how to tune us in and help us connect with the experience that's in our heart. He helps me find my way back to a place inside that nourishes me and makes me feel taken care of," Marsh says. Carol Robinson, from the UK, says practising what Maharaji preaches "gives me a real focus in life. He's not harming me, he's not harming anyone". The Gulfstream at Brisbane Airport (a photograph of it sitting on the tarmac was posted on the www.ex-premie.org web-site yesterday) will soon carry him home. But you get the impression that the story, and the hostility surrounding a peace guru, will run and run. Back at Ivory's Rock, the conference is today culminating and thousands of tent pegs will come out of the rich soil. For followers like Vic Marsh, the Maharaji event was "like a huge celebration". |

|